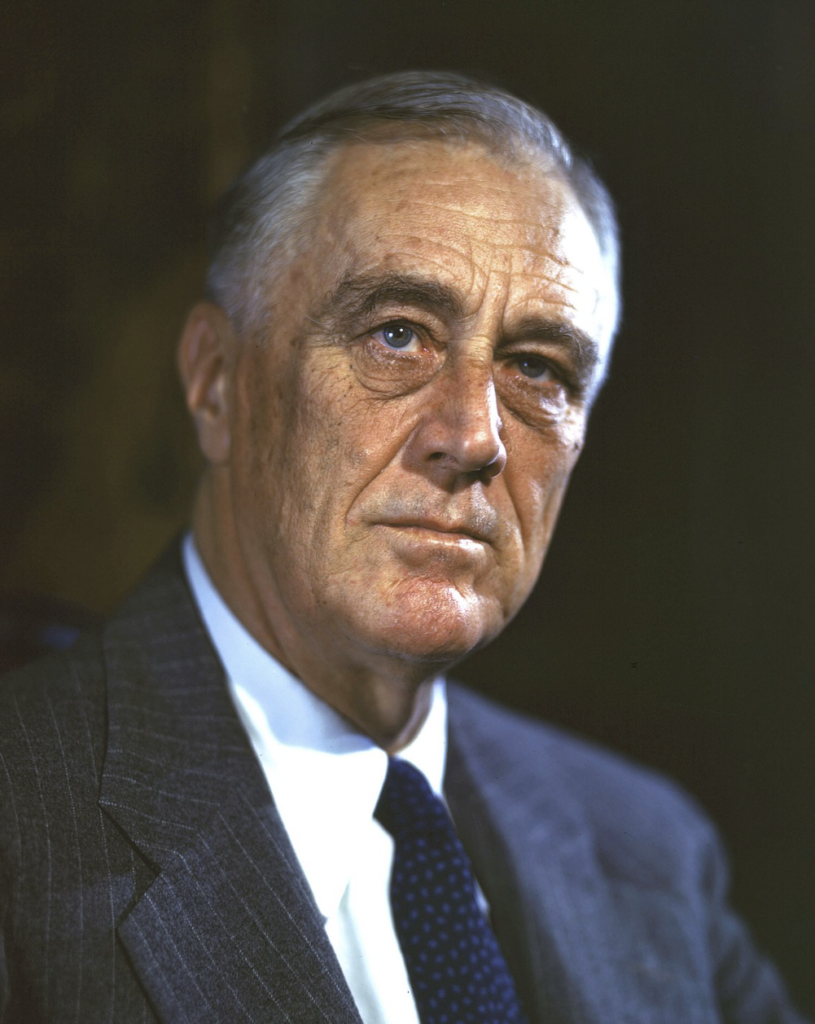

“What our servicemen and women want, more than anything else, is the assurance of satisfactory employment upon their return to civil life. The first task after the war is to provide employment for them and for our demobilized workers … The goal after the war should be the maximum utilization of our human and material resources.“

– President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s Statement to Congress on June 22, 1944

While the notion that veterans deserve/are owed financial support after their service originated in this country in the era of the Revolutionary War, the structures of support and their visibility have evolved significantly over the passing of multiple G.I. Bills with each war. Higher education institutions were (and still are) influenced by governmental financial assistance. Originally, such institutions saw student veterans primarily as a source of financial gain and took advantage of veterans early on in history. Although this is not to say that all higher education institutions take advantage of their student veterans, in 2010, 23 % of veterans that utilize the G.I. Bill do so at for-profit institutions, and it is worth scrutinizing the history of veteran benefits to get a better glimpse at the treatment and perceptions that such institutions have on veterans.

The Post-American Revolution Era

The Continental Congress passed the first

pension legislation, whereby it provided half pay for Continental Army officers and for those

who became disabled and were incapable of making a living. In 1806, the pension legislation

was extended to include disabled veterans of state troops and militia service.

The Pension Act

In March 1818, Congress passed the Pension Act, a monumental bill that hoped to cement public memory of the American Revolutionary War. The Act created the first national military pension establishment, run by the War Department, and broke Congressional resistance to awarding lifelong pensions. Yet, the Act wasn’t inclusive because it excluded tens of thousands of veterans of the American Revolutionary War as it targeted only particular types of veterans who served for at least 9 months in the Continental Army. Even though the Act was exclusive, the passing of the Act signified a shift towards a more inclusive understanding of military service that would expand well into the Civil War era and beyond..

The Aftermath of the War of 1812

Before the War of 1812, civilians would view servicemen as the dregs of society and something to be feared and despised. After the war, public opinion shifted to see “suffering soldiers” (common rhetoric during those times to describe veterans) as patriotic, heroic, and in need of assistance, regardless of the class they came from. The pension bill intended to promote political harmony in a nation divided by war and hoped to unify the nation. However, this hope was based on Congress’s idea that this program would be inexpensive and brief. In reality, the program turned out to be “long, costly, and divisive” and led to an amendment in 1820 that converted the program into a hybrid of pension and poor-law provisions.33

1890 Dependent Pension Act

The 1890 Dependent Pension Act was the biggest single change to happen to the pension systems during the time. Because the Civil War was mostly fought by laborers and farmers, whose livelihood depended on pensions for support should they be disabled or injured after the war, the Act expanded eligibility to those who were unable to do labor after the war, even if the disability was not a direct result of the war. In 1901, it was further added that old age was considered a disability.

Benefits under World War I

On October 6, 1917, the federal government made a radical change from the existing framework found during the Civil War. If the Civil War pension system would have remained in effect, with no new legislation, service-connected disabilities would have still applied to veterans. The federal government began to adjust for compensation in proportion to the degree in which the veteran was injured, and his ability to earn a wage after service, and to the size of the dependent family, as opposed to just giving out a pension.

The Great Depression

In 1924, Congress had awarded veterans of World War I with certificates redeemable in 1945 for $1000 dollars each, but because many veterans lost their jobs and/or fortunes, they wanted Congress to redeem the certificates early. Congress couldn’t afford to do this and went even further as to renege on veteran bonuses. Eventually, this led to the Bonus March of 1932, where over 43,000 veterans and family members protested. Finally, Congress authorized the bonuses, which were almost 13 years overdue.

Franklin D. Roosevelt and the GI Bill Era

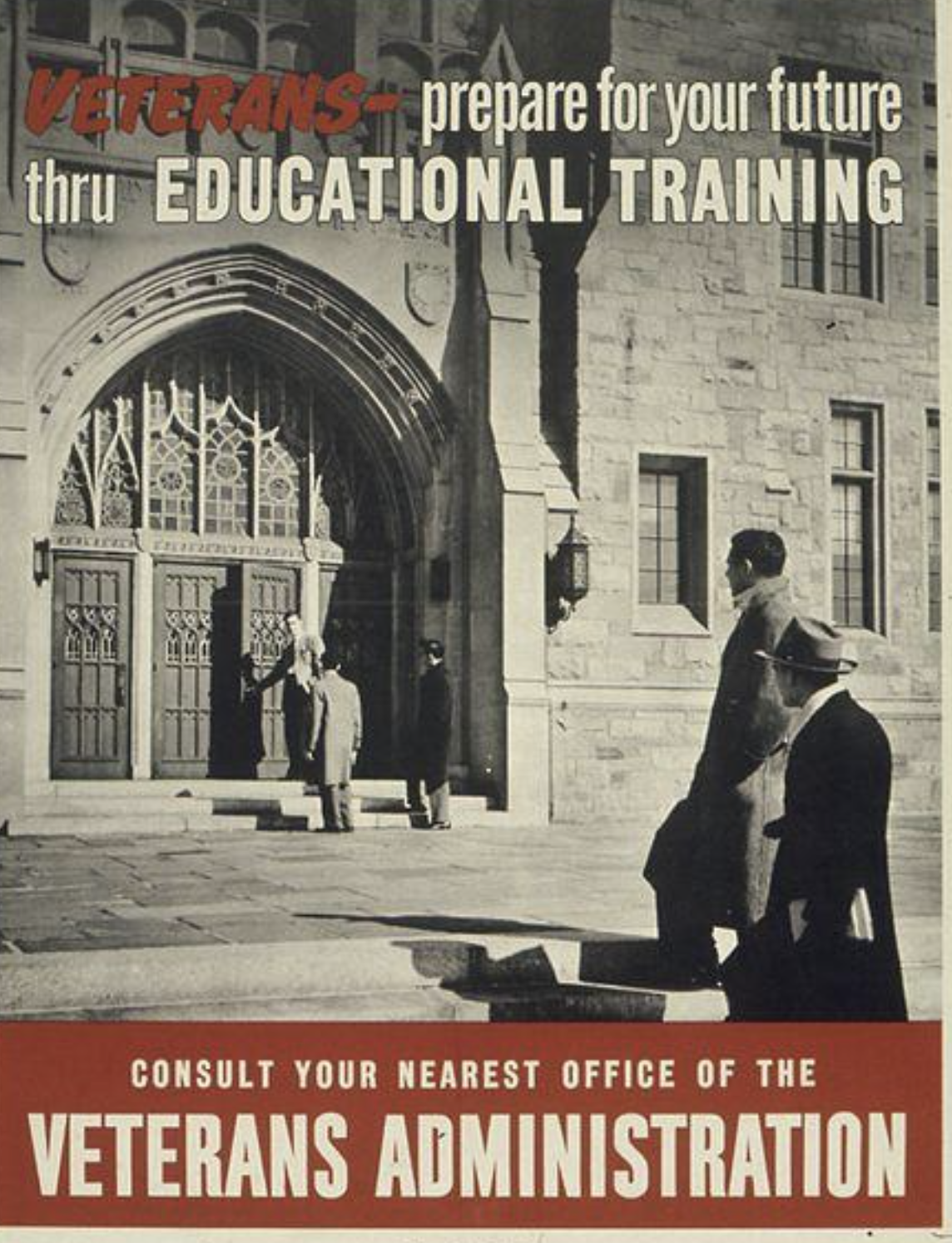

When FDR was elected, he was cognizant of the fact that most soldiers that fought were young men who had forsaken college or vocational training and if they returned home would not have the proper resources to adjust to civilian life. FDR’s commitment to soldiers led to the signing of the Servicemen’s Readjustment Act, also known as the G.I. Bill, into law on June 22, 1944. Known as one of the most revolutionary pieces to address higher education, the G.I Bill assisted millions of veterans transitioning into post war society. The educational aspect of the G.I Bill is but one part of the comprehensive package of benefits that the bill set forth. Other than education, the bill would also grant more than 15 million World War II veterans access to home and small business loans, unemployment insurance, and other benefits.

World War II era continued

The G.I. Bill in the second World War era regarded gender and race in neutral terms, as long as those who served were discharged honorably and served at least ninety days, the G.I. benefits would apply. However, considering the era at the time was filled with anti-semitism, bigotry, and gender inequality, even though the G.I. Bill provided equal benefits on paper, it did not mean that the results were equitable. Although the bill democratized higher education, it mostly did so for white male populations because of largely anti-black views during this time period.

The Korean GI Bill

In the 50’s it was found that educational institutions were committing fraud by raising tuition rates in an attempt to maximize their financial returns from the large veteran populations they allowed in. The testimonies heard ultimately influenced Congress’s views towards providing Korean war veterans benefits. The G.I. Bill benefits under the Korean War era ended up with a net decrease as the 52-20 benefit, the original benefit for World War II veterans, ( $20 dollars a week for 52 weeks) was reduced to $26 for 26 weeks. There was also a radical departure from the previous bill in that instead of funds being disbursed to institutions, like colleges and universities, funds were directly given to veterans at a flat rate of $110 per month to cover all related costs, like tuition, books, and living expenses while studying.

The Cold War Era

Even though the Korean G.I. Bill helped set a precedent in form and function for future G.I Bills, the Cold War era was a highly debated period when it came to veteran benefits. In fact, the concept of the Cold War G.I bill was received coolly by the Eisenhower administration because of the debates surrounding non-combat veterans and whether they should receive the same benefits as those who served in combat zones. Eisenhower was opposed to equal treatment saying: “Those who serve in peacetime undergo fewer rigors and hazards than their usual comrades,” he noted. “Such benefits are not justified because they are not supported by the conditions of military service.” Attempts to reintroduce this idea were numerous throughout the Cold War period but succeeding administrations remained unmoved.

Readjustment Benefits Act of 1966

It was only with the deteriorating situation in Vietnam, and to show solidarity with the veteran population, did the Johnson Administration pass the Readjustment Benefits Act of 1996, which extended benefits to all members serving, whether during peacetime or war, during the Korean War era. However, the Johnson Administration realized the limitations of the 1966 G.I Bill. “The central flaw in the 1966 G.I. Bill was that it was crafted with the average Cold War veteran in mind, not the combat veteran who might have far greater readjustment needs and expectations.” In other words, if a veteran came back from a particularly traumatic combat zone, the benefits provided would fall short as compared to someone whose service was done during relative peacetime. To try and address this flaw, Johnson passed the Vietnam Conflict Servicemen and Veterans’ Act of 1967, which “incorporated a thirty-dollar increase in veterans’ education benefits and provisions to help disadvantaged veterans finish their high school education without affecting their college benefits.” Months later, further amendments were made so that all single veterans received a monthly stipend of $130 but this time with proportional increases for dependents. Yet, a big problem remained, the bill did not create distinctions between Cold War Veterans and Vietnam Veterans.

The Vietnam War

Numerous studies also showed the combat experience of soldiers during Vietnam revealed conditions that were at least as brutal as the conditions seen in World War II or Korea, with many Vietnam Veterans returning with readjustment issues as great, if not greater, than those who returned from other conflicts. The bill of 1967 and the subsequent amendments fell short on previous G.I provisions. Although President Johnson further signed significant student veteran legislation on October 23, 1968, which provided one and a half months of benefits for every month a veteran served (but only if they served over 18 months), the G.I under the Vietnam era did not provide the same support to Vietnam veterans as the G.I. did to World War II veterans.

The Montgomery GI Bill Era

Congress was worried. They worried that with the expiration of the Vietnam G.I. Bill that the military would not be able to recruit and retain qualified men and women. So it came as no surprise then that because of the failure of the Vietnam Era G.I. Bill to fully accommodate its veteran population and the public’s negative sentiment about the war, the 60s and 70s saw recruiting problems significantly increase. The real solution came during the fall of 1980. Sonny Montgomery, a veteran of World War II, recognized that because most potential recruits weren’t even finishing high school, the educational shortfall had a significant impact on the low retention numbers in the military. The Montgomery G.I. Bill was a shift from rewarding educational benefits for service to using these benefits to enhance the appeal of being a recruit for the military.84 The new bill also had higher selectivity requirements, with a restriction against those serving without high school diplomas. Another big component of the bill was that it allowed “participants to have their pay reduced by $100 a month for their first 12 months on active duty and in exchange, the VA would pay them up to $400 a month for 36 months of college or other training.” One difference from previous G.I Bills was that dependent children or spouses were not allowed to use this benefit.

The Post 9/11 GI Bill

When the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq followed, the Montgomery Bill was the primary educational benefits bill for veterans. However, Congress recognized that as the wars ended, there would be a significant reduction in military size, as many military members choose to discharge. The Post 9/11 G.I. Bill grew out of this recognition that there would be a large veteran population that would need assistance. The Post 9/11 G.I. Bill was implemented in 2009 in the same spirit as World War II G.I. Bill. While the World War II G.I. Bill is considered to be one of the most comprehensive benefits plans for veterans, the Post 9/11 G.I. Bill is seen as the most generous educational benefits plan ever offered to military veterans. “The size of the benefit expansion makes it one of the largest increases in financial aid in decades: benefits pay for in-state tuition, fees, a monthly housing allowance, and a generous stipend for books and supplies.” The Post 9/11 G.I Bill is also unique in that it accounts for geographic variation, meaning it adjusts for the cost of living and in-state tuition based on the state that the veteran resides in or will go to.

The Forever Bill

n 2017, President Trump signed a new law that would further bring significant changes to educational benefits for active- service members, veterans, and their families. Known as the Forever Bill, the bill will no longer place an expiration date on the Post 9/11 G.I. Bill. Previously, to claim benefits under the Post 9/11 G.I. Bill veterans had to use the bill within 15 years of their last 90 day period of active duty, now the requirement went away. A significant aspect of the bill is that school certifying officials must now be trained if there are more than 20 veteran students on campus. There is also more money and scholarship opportunities for student veterans pursuing STEM degrees as well as an increased opportunity to be eligible for the Yellow Ribbon Program, which will sometimes help cover the difference between costs.